by Hakyung Sim

The month of October was full of treats for theatergoers in Seoul. Along with the usual domestic performances, works of foreign directors and companies were brought to local stages by festivals such as SPAF (Seoul Performing Arts Festival) and SIDance (Seoul International Dance Festival). Though I’m not dance-savvy at all, the array of Western contemporary dance performances interested me.

Above all, Sfumato, a work presented at SPAF by French choreographer Rachid Ouramdane and his company L’A, appealed with its slogan: “a sociopolitical dance-documentary about climate refugees”. It was introduced that Ouramdane's trip to Vietnam, where he witnessed refugees from a tornado, had inspired him. Sure, the widely anticipated use of water on stage was another appealing point. Seeing several productions recently with water on stage, however, had made “water” less sensational for me; I rather focused on how it was used, or what effects it gave on the overall experience.

Smoke, Wind and Rain

As darkness faded away, a man and a woman lay scattered on stage. From each of their bodies, smoke fumed up, creating a cloudy mist or veil over what had been darkness. Just like Da Vinci’s technique of sfumato, Ouramdane's smoke blurred the boundaries between stage and audience; the real and the imaginary; here and there.When a female dancer appeared on stage by spinning, I immediately recognized her as “wind”. Her spinning was extraordinary. How could someone turn so well, in such seemingly breathless manner? It wasn't like a pirouette as in ballet; the movement was less refined or graceful, yet amazingly precise and absolutely mesmerizing. I thought, there is something about circular movements in dance – the magic circle – that definitely allowed some kind of mysterious or even magical effects to take place. Whatever it was, it enchanted me. Though sitting on the second floor, I was completely absorbed into the fantasy that the stage created. Along with the visual awe that the spinning dancer gave, the swishing, threatening sound of her arms – I was aware of the amplifiers inside her sleeves – stimulated all senses. This wasn't a pretty turning dancer to look at. This was the hurricane.

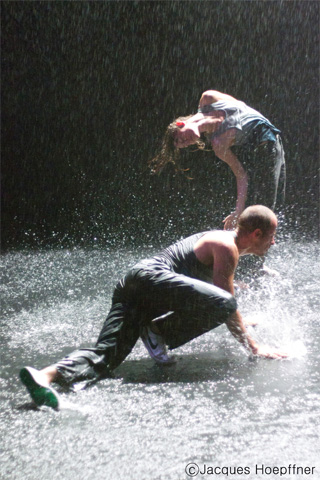

Then it rained on the stage, and the spectacle was at its aesthetic peak. The dropping sound of the torrential rainfall was one thing, and the reflection from the gathered water was another. It is said that listening to the sound of water calms people down. The sound created by water falling on stage surely did that, but to the extent of being ominous. As the water started to gather on the floor, its wavering movements were reflected upon the ceiling, naturally creating a supernatural backdrop for the performance to follow.

Blurred Movements and Doubtful Moments

In the perfectly enchanting atmosphere on stage, wet dancers ran, glided, stomped and did their thing across the floor in rain. A pianist appeared now and then to play the soaked piano on stage. The dancers were doubtlessly highly-trained and obviously knew what they were doing. Their movements were “vaguely” representative of any “likely” scenes of the natural disaster that they were “possibly” depicting, yet nonetheless beautiful to watch. I put those words in quotation marks, not in any satirical mood but out of concern for the legitimacy of my prescribed expectation for this work of art. Sfumato indeed made me think about what it means to appreciate art.So what does it mean to appreciate art? Was I or was I not appreciating a work of art when I anticipated some sociopolitical message from this dance performance that supposedly raised “sociopolitical issues”? There was a narration or a libretto as they called it, which was played over the speakers throughout the performance, and some video clips of interviews and photographs projected on the screen every now and then. Ouramdane had obviously used multimedia well in his work, especially to deliver the narrative of the climate refugees. However, I couldn't help but feel that the dance as a medium itself and the other media were disintegrated in the work as a whole. So what if the stories of hurricane victims were told through the libretto? What if we saw the face of an old man, who may or may not be the actual victim?

What bothered me the most throughout was the grand piano on stage, neglected in the pouring rain. Music was played over the speakers as well, so its function was obviously not only to produce music. I had heard earlier that Ouramdane was especially shocked and inspired by a wrecked piano in the aftermaths of the hurricane in Vietnam, and wanted to share that experience through his work – at the risk of ruining a perfectly fine grand piano. I couldn't help but cringe at the thought of the cost, and the ghostly faces and stories of the Vietnamese hurricane victims – and this led me to the question I posed earlier. What does it mean to appreciate art? Was I being uncivilized and stingy at the cost of art, which should be priceless? What does art do for us anyway, when lives of people are out there, not affected by art at all?

* * *

While I do acknowledge that it isn't for art to be educational or edifying, the questions of art’s functions or the meaning of appreciating it have been on my mind since. I believe this was because seeing Sfumato was a purely aesthetic experience for me, apart from its supposed relations with any “sociopolitical” topics. Yet I still wonder why I felt uncomfortable, sitting and watching the French choreographer’s work, performed by French dancers, depicting the experiences of Vietnamese hurricane refugees. Unlike Da Vinci's technique of having the form float up from the blurred borders and eventually create a more natural yet clear form, Ouramdane's Sfumato left me in a smoke of doubts and questions.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kxYj2thg_g0